Google’s Messages Update Just Made Android More Like iPhone

Android’s blue bubble moment—what to know.

Android’s blue bubble moment—what to know.

In the era of the gig economy, what role do identity verification and authentication technology play? Answer by Catherine Porter.

This week’s Apple headlines; the impact of US tariffs on the iPhone, a surprise iOS update, BBC attacks Apple News, Instagram finally arrives on the iPad, and more…

Australian workers have to overcome some significant barriers in navigating their careers.

Some may lack the training or work experience opportunities needed to make themselves stand out and take the next step. Others may be extensively qualified, but face limited new job or promotional opportunities relevant to their skill set.

But there’s another common barrier that’s often overlooked: post-employment restraints. Among the most well-known are non-compete clauses, but these aren’t the only kind.

These tools are designed to protect employer interests. But their widespread use has far-reaching consequences for job mobility, wages and innovation across Australia.

Our new research, which was commissioned by the Department of Treasury and conducted by researchers at Queensland University of Technology, set out to examine how these agreements are impacting Australia’s workforce.

We zeroed in on two very different occupational groups – hairdressers and IT professionals. Our findings point to an urgent need for regulatory reform in Australia. But we also offer solutions that could better balance business needs with worker rights.

Post-employment restraints are contractual clauses that restrict what workers can do after leaving their jobs.

One common type are non-compete clauses, which prevent workers from joining competitors or starting their own businesses, usually (though not always) in the same industry.

There are also non-solicitation agreements, which restrict them from approaching former clients or colleagues.

And non-disclosure obligations can limit the use of confidential information concerning the employer’s business – even when created by workers themselves.

Businesses argue these clauses help them safeguard their proprietary interests, such as hard-won client relationships, trade secrets and intellectual property.

However, their application is not limited to high-level executives or sensitive roles. Such restraints are more common than many realise.

Data cited in our report from businesses with 200 employees or less confirms previous Australian research: at least one in five businesses use non-compete, non-solicitation of clients and non-solicitation of co-workers clauses. The number is even higher if non-disclosure agreements are included in the list of restraints.

Overall, half of all Australian workers are reported to have post-employment restraints – including many in low-paid jobs.

As former Fair Work Commission President Iain Ross has pointed out, this raises critical questions about fairness and the broader impacts on the labour market.

Hairdressing is a predominantly female, low-wage profession. Our interviews with hairdressers reveal the outsized impact that post-employment restraints can have on vulnerable workers.

Restrictions typically include bans on working within a certain radius of their former salon, taking clients to a new employer, or starting their own business.

Many interviewees only learned about these restrictions after accepting a position or deciding to leave. Some reported being barred from telling clients of their departure or facing demands to pay penalties if clients followed them to a new salon.

The personal relationships hairdressers form with their clients are central to their work and professional identity. However, these relationships often become battlegrounds when employment ends.

Hairdressers explained the difficulties that often arose from becoming “friends” with clients. As one put it:

As soon as you leave, it’s almost harder than a breakup.

Financially, these restrictions exacerbate the already precarious conditions in the hairdressing industry.

With limited opportunities for wage growth, many hairdressers establish their own businesses or rent chairs in salons for greater independence.

Yet, non-compete clauses often delay these plans. Hairdressers are then forced to accept lower-paying positions or leave the profession entirely.

Social media has added a whole new layer of complexity. Hairdressers are often required to use their personal social media accounts to promote their employer’s business, only to have their posts deleted or accounts locked when they leave. This can erase years of professional work and connections.

Many young hairdressers we spoke to expressed particular frustration that their social media presence, cultivated under the salon’s brand, could not be carried forward to new roles.

Our study found while hairdressers face restrictions on their mobility and client relationships, IT professionals face obstacles that limit their ability to innovate.

IT professionals often develop new technologies, software or processes, sometimes in their own time. However, contracts often claim ownership of these innovations for the employer.

We found non-disclosure agreements, non-compete clauses and intellectual property ownership terms are all common in the industry.

This environment discourages entrepreneurial ventures and independent projects, even as the industry demands agility and creativity.

As one participant explained:

It’s made me pause multiple times, made me think about not developing a code that you’re interested in just for your own development.

Professionals reported feeling “locked in” to roles, unable to pursue side projects or start their own businesses without risking legal action.

Non-compete clauses in IT contracts also restrict job mobility when professionals cannot join competitor companies or use their expertise in new roles.

This impacts not only individual workers but also the broader industry, as firms struggle to recruit skilled talent.

Paradoxically, some employers actively poach talent from competitors while enforcing non-compete clauses against their own staff.

By limiting job mobility, post-employment restraints contribute to wage stagnation and reduce workers’ bargaining power.

Australia’s regulatory approach to this issue lags behind other countries. There are no formal limits on the length or breadth of restraints, just a vague test of “reasonableness” that makes it hard to know what is permissible, without costly litigation.

In the United States, California has banned non-compete clauses outright, fostering a thriving tech industry. In Europe, companies like Germany impose strict limits on the duration of restraints and require employers to compensate workers during the restricted period.

These models demonstrate that balancing employer interests with worker rights is possible and can yield positive outcomes.

One option for policymakers in Australia would be to impose new restrictions on the scope and duration of restraints to ensure they serve legitimate business interests without unduly restricting workers.

Employers could be required to provide plain-language explanations around these restrictions at the time of hiring and compensate workers for the duration of any restraint, as seen in some European models.

Post-employment restraints are a double-edged sword. While they may protect legitimate business interests, their overuse undermines job mobility, innovation and worker wellbeing.

Read more:

Would a mandatory five-day working week solve construction’s work-life balance woes?

![]()

Paula McDonald receives funding from the Australian Research Council and the Commonwealth Department of Treasury.

Andrew Stewart receives funding from Commonwealth Department of Treasury.

The advent of generative artificial intelligence has sent shock waves across industries, from the technical to the creative. AI systems that can generate viable computer code, write news stories and spin up professional-looking graphics have inspired countless headlines asking whether they will take away jobs in technology, journalism and design, among many other fields.

And these new ways of doing work and making things raise another question: In the era of AI, what does it mean to be an inventor?

Among technologists who build digital tools or programs, it is increasingly common to use AI as part of design and development processes. But as deep learning models flex their technical muscles more and more, even highly skilled researchers who are using AI in their work have begun to express concerns about becoming obsolete.

There is much debate about whether AI can augment human creativity, but emerging data suggests that the technology can boost research and development where creativity typically plays an important role. A recent study by MIT economics doctoral student Aidan Toner-Rodgers found that scientists using AI tools increased their patent filings by 39% and created 17% more prototypes than when they worked without such tools.

While this study indicates that AI seemed to help humans be more productive, it also showed there was a downside: 82% of the surveyed researchers felt less satisfied with their jobs since implementing AI in their workflows. “I couldn’t help feeling that much of my education is now worthless,” one researcher said.

This emerging dynamic leads to a related question: If a scientist uses AI in order to build something new, does the output still qualify as an invention? As a legal scholar who studies technology and intellectual property law, I see the growing power of AI shifting the legal landscape.

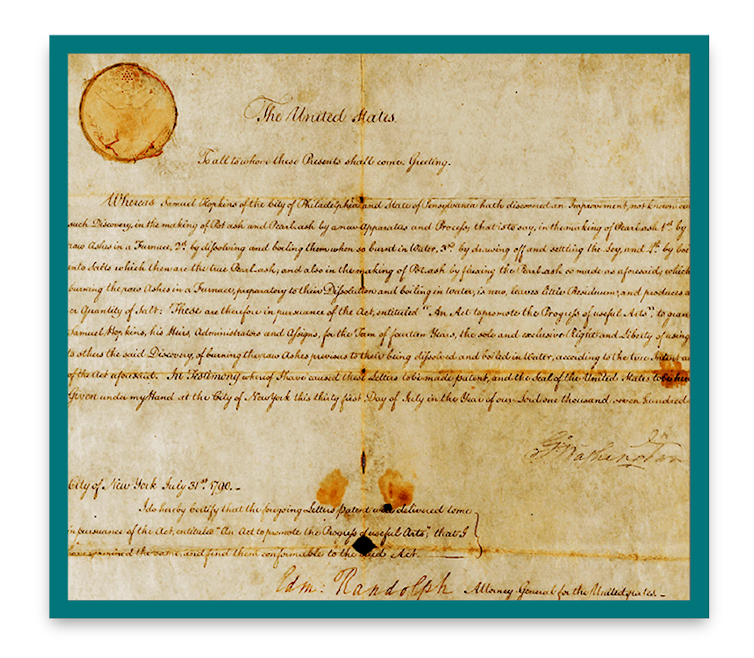

In 2020, the United States Patent and Trademark Office refused to list the AI system DABUS, which purportedly designed a food container and a flashing emergency beacon, as an inventor on patent applications. Subsequent court rulings clarified that under current U.S. law, only humans can be listed as inventors, but they left open the question of whether inventions developed by scientists with the help of AI qualify for patent protection.

The concept of inventorship and legal protections for inventions have deep roots in the U.S. The Constitution explicitly protects the “exclusive rights” of authors and inventors “to their respective writings and discoveries,” reflecting the framers’ strong conviction that the state should protect and encourage original ideas.

U.S. law today defines an inventor as a natural person who has conceived of a complete and operative invention that can be used without extensive research or experimentation. An inventor must do more than follow routine instructions – they must make an intellectual contribution in producing something novel.

That contribution can be a key idea that sparks the invention or a crucial insight that turns the concept into a working product. If a person’s input is routine or just explains what’s already known, they are not an inventor.

To what extent can or should AI become part of the invention process? The release of AI applications such as ChatGPT in 2022 introduced the public to large language models and sparked renewed debate about whether and how AI should be used in the inventive process. That same year, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit heard a case that tested whether AI could be named as an inventor on a patent application.

The court concluded that under U.S. law, inventors must be human beings. The ruling reaffirmed the idea that Congress intended to encourage human beings, not machines, to invent. This idea remains foundational to current patent policy.

In light of the court’s decision, in 2024 the United States Patent and Trademark Office updated its guidance to clarify the role of AI in the inventive process. The guidance reaffirms that an inventor must be human. However, the Patent and Trademark Office explained that the policy did not preclude inventors from using AI tools to assist in the research and development of inventions. This approach acknowledges how the rapid development of AI technologies has allowed researchers to make exciting breakthroughs.

Policymakers seem to understand that if the U.S. is to continue to lead the world in innovation, the mythology of a sole inventor toiling away in a garage and relying on pure intellect must evolve to account for the value of AI tools that research has proven make humans more productive.

Nevertheless, since only human beings can be named as inventors on a patent, current policy does not quite answer the question of who or what should get credit for doing the work. Despite a growing trend where researchers are expected to disclose whether they’ve used AI tools, for example in academic papers, the U.S. patent system makes no such demand.

Regardless of AI’s role in the research and development process, a U.S. patent will list only the names of human inventors so long as those humans made a significant contribution to the invention. As a result, current policy is not concerned with how to recognize the contributions of AI. AI is considered a tool like a microscope or a Bunsen burner.

Given this shifting legal landscape, I see that U.S. innovation policy is at a crossroads. The Patent and Trademark Office’s guidance reaffirming human inventorship and simultaneously embracing AI as an innovation tool is only a year old. It is unclear how the Trump administration’s forthcoming action plan to “enhance America’s global AI dominance” will affect this guidance.

Some observers expect the rate of scientific discovery to increase dramatically with the assistance of AI tools. But if the majority of those same productive researchers enjoy their jobs less, is the act of inventing being encouraged as the framers envisioned?

Current U.S. policy attempts to strike a balance and recognize the concept of personal ingenuity, stemming from the principle that for an invention to be patented in the U.S., a human must have led the way. Yet the guidance also implicitly acknowledges that AI can lend a helping hand in modern research and development. Whether and how policymakers maintain this balance – and how leaders in industry and science respond – will help shape the next chapter of American innovation.

![]()

W. Keith Robinson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The success of the Chinese AI firm DeepSeek shocked financial markets and major US tech firms in January 2025. But it shouldn’t have come as such a surprise.

Because, for decades now, plenty of companies in China have been developing competitive advantages that enable them to make remarkable progress. This involves a different strategy to that of many big western firms that rely on things like branding – like Apple – and exclusive technology – like Nvidia – to succeed.

Instead, these less well-known Chinese companies have focused on delivering more innovation faster and cheaper. And our research suggests that they have been able to achieve this by being much more adaptable in how they do business.

So DeepSeek may not be alone as a gamechanger. Here are four more Chinese firms looking to disrupt the global economy in a similar way.

DJI Innovations makes low-cost drones that produce aerial photography and videos. Founded in 2006 by Frank Wang (who became Asia’s youngest tech billionaire at the age of 36), the company develops camera technology and software as well as engineering drone systems used in industries including agriculture and defence. Its technology has been used in the filming of shows like Better Call Saul and Game of Thrones.

DJI’s cutting-edge research and development involves highly sophisticated automated assembly lines that make more for less cost. This has led to rapid international expansion and foreign partnerships, making the company a dominant player which is tough to compete against.

A DJI Innovations spin-off founded in 2016, Unitree Robotics specialises in high-performance quadruped and humanoid robots, as well as components like robotic arms. These products incorporate artificial intelligence and have many applications in consumer and industrial markets.

But in a sector where progress can be slower than we might expect, Unitree’s rapid development cycles –from initial idea, through development and testing, to commercialisation – give it an edge over rivals. This cycle speed is achieved through highly digitised processes, and large highly skilled development teams, which place it ahead of many rivals.

For example, in 2024 one of the firm’s humanoid robots (already capable of soldering and cooking) set a new walking speed record of 3.3 meters per second. And in early 2025 the company’s robots performed a traditional Yangko dance alongside humans.

Game Science is a Chinese video games firm founded in 2014. Its August 2024 release of Black Myth: Wukong, an advanced role-playing video game inspired by the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West, is one of the fastest-selling games of all time, with revenues of over US$1.1 billion and over 25 million copies sold to date.

This success demonstrates the firm’s ability to create products that incorporate Chinese cultural elements that also appeal to global tastes. This is partly down to the company’s prolific data analysis capabilities, allowing it to incorporate vast quantities of feedback from players into its design decisions.

That input gives it a big advantage over competitors, moving beyond the old Chinese export model of making cheap versions of western products. Instead, it offers innovative products that are also cheaper, contributing to China’s growing presence in the global gaming market.

Yonyou was set up in 1988 to offer business and accounting software to Chinese companies. It now dominates the market in the country and has spread to Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia. Beyond Asia is the next goal.

The firm’s success hinges on its ability to optimise its products for local customers while avoiding premium pricing. It understands that business systems vary geographically according to things like local culture, customs and consumer taste.

Yonyou’s proposition is simple but very effective: to develop software that varies to serve idiosyncratic local needs, knowing that this will work better than the one-size-fits-all products available from global competitors.

This has led it to create popular and specific software for industries including retail, education, finance and construction. The company’s expertise lies in challenging the conventional wisdom that customised products come at a high cost.

Each of these four Chinese firms clearly understands the advantages to be gained from innovative technology and good strategy, which are both within their control. What they cannot control are the geopolitical factors to do with international trade and the global economy – which makes the future uncertain.

But continuing to work to their particular strengths will make it likely that they – and plenty of others like them – go on disrupting global markets.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

South Africa has about 700 state-owned enterprises. They operate across sectors like transport, energy and public utilities, and some are among the largest employers in those sectors.

Entities like these are created and controlled by a country’s government to provide essential services and drive economic development. In South Africa, they were formed in the 20th century, when the government recognised the need to support local industries by providing services such as rail transport, financing and electricity.

As the country industrialised, more state-owned entities were established to serve businesses and communities and to create jobs. In the early 21st century they were also tasked with generating revenue for the state.

But when South Africa’s state-owned enterprises are mentioned in civil society discourse, it’s often for all the wrong reasons. They’re beset by poor service delivery, financial difficulties and allegations of corruption. Their performance has significantly deteriorated in the past 15 years. Unclear mandates, poor management, and insufficient infrastructure and resources are among the reasons.

This has overshadowed their potential to contribute to research, development and innovation which could support economic growth.

We at the Centre for Science, Technology and Innovation Indicators at the Human Sciences Research Council have conducted research to identify what state-owned enterprises need to do to bolster research and development (R&D) and innovation.

We used three state-owned enterprises as case studies. They operate in different sectors: forestry, aviation and energy. They were chosen for their apparent innovation through R&D or other activities. We identified five ways to assess whether a state-owned enterprise is ready and able to achieve its objectives via R&D and innovation: its human capabilities, technological capability, collaborations and partnerships, research infrastructure and governance.

The three organisations successfully integrated R&D and innovation into their strategies. But improvements were needed in the areas of capacity, resources and organisation.

Although state-owned enterprises are unique entities, the framework we developed using those five areas helped us to understand their innovative traits as players within a specific sector. It is a valuable assessment tool that can guide individual state-owned enterprises and policymakers in improving the enterprises’ R&D and innovation outputs. Ultimately, this might contribute to economic growth and the development of specific sectors.

The South African Forestry Company SOC Limited, founded in 1992, was one of the three organisations we studied. It has a dual mandate. One is commercial, focused on timber harvesting, processing and related activities, both nationally and internationally. The second is socio-economic: to deliver returns to its shareholder, the Department of Public Enterprises, while promoting rural economic development.

In South Africa, the company manages 189,760 hectares of forest, including 121,585ha of commercial plantation. In Mozambique, it manages 82,547ha of forest; 15,258ha of this is commercial plantation. It processes about 10% of South Africa’s logs and produces over ten million seedlings annually.

Here’s how the organisation performed in 2022 (the year we conducted our research) in the five assessment areas.

Human capacity: The R&D team makes up less than 1% of its workforce of about 5,000 people. The organisation’s training academy provides a wide range of programmes for employees and the communities close to its operations. It supports capacity building in the sector through postgraduate bursaries.

Technological capacity: The organisation’s ability to use R&D and technology to achieve its business goals spans the entire timber value chain. The organisation also has non-timber capabilities. These include community-based forestry, training and eco-tourism.

Collaboration: There are strong collaborations with universities, research councils, communities and global and local organisations. This helps to build capacity and to solve different operational problems. It also grows relationships with communities.

Research infrastructure: The company conducts R&D at its nursery in Tweefontein in the Western Cape province and R&D centre at Sabie in Mpumalanga province. For instance, timber tissue culture research is done at the centre to improve lumber yields over time. The centre has state-of-the-art equipment and more is being sourced.

Governance: The organisation recognises the importance of R&D and continues to invest in it. An innovation portfolio is part of its executive structure. However, it hasn’t achieved its capital investment goals. It also does not have strategies for intellectual property management or technology transfer.

All three of our case studies had made R&D and innovation activities part of their strategic planning. They also had clear examples of innovative performance and did well when it came to collaboration.

Still, there was a lot of room for improvement. All three entities needed to hire more researchers and technicians. All three also face the challenge of using the technological knowledge and systems they have developed over years towards generating income from innovation. This can be done through commercialising intellectual property.

Research infrastructure is an area of concern for all three entities. They need more long-term investment. We also found that long-standing R&D programmes needed to be refreshed. More proactive approaches to innovation and the commercialisation of intellectual property could help.

We believe that our analysis and the resulting indicators can be used by all South African state-owned enterprises to assess what they need to achieve more R&D and innovation. It’s a tool for them to track their progress in becoming more innovative, and going beyond their core service delivery mandates.

![]()

Jacqueline Borel-Saladin works for a research council that receives funding from the Department of Science Technology and Innovation.

Nazeem Mustapha works for a research council that receives funding from the Department of Science Technology and Innovation.

Jerry Mathekga works for a research council that receives funding from the Department of Science Technology and Innovation.

Imagine a not-too-distant future where you let an intelligent robot manage your finances. It knows everything about you. It follows your moves, analyzes markets, adapts to your goals and invests faster and smarter than you can. Your investments soar. But then one day, you wake up to a nightmare: Your savings have been transferred to a rogue state, and they’re gone.

You seek remedies and justice but find none. Who’s to blame? The robot’s developer? The artificial intelligence company behind the robot’s “brain”? The bank that approved the transactions? Lawsuits fly, fingers point, and your lawyer searches for precedents, but finds none. Meanwhile, you’ve lost everything.

This is not the doomsday scenario of human extinction that some people in the AI field have warned could arise from the technology. It is a more realistic one and, in some cases, already present. AI systems are already making life-altering decisions for many people, in areas ranging from education to hiring and law enforcement. Health insurance companies have used AI tools to determine whether to cover patients’ medical procedures. People have been arrested based on faulty matches by facial recognition algorithms.

By bringing government and industry together to develop policy solutions, it is possible to reduce these risks and future ones. I am a former IBM executive with decades of experience in digital transformation and AI. I now focus on tech policy as a senior fellow at Harvard Kennedy School’s Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government. I also advise tech startups and invest in venture capital.

Drawing from this experience, my team spent a year researching a way forward for AI governance. We conducted interviews with 49 tech industry leaders and members of Congress, and analyzed 150 AI-related bills introduced in the last session of Congress. We used this data to develop a model for AI governance that fosters innovation while also offering protections against harms, like a rogue AI draining your life savings.

The increasing use of AI in all aspects of people’s lives raises a new set of questions to which history has few answers. At the same time, the urgency to address how it should be governed is growing. Policymakers appear to be paralyzed, debating whether to let innovation flourish without controls or risk slowing progress. However, I believe that the binary choice between regulation and innovation is a false one.

Instead, it’s possible to chart a different approach that can help guide innovation in a direction that adheres to existing laws and societal norms without stifling creativity, competition and entrepreneurship.

The U.S. has consistently demonstrated its ability to drive economic growth. The American tech innovation system is rooted in entrepreneurial spirit, public and private investment, an open market and legal protections for intellectual property and trade secrets. From the early days of the Industrial Revolution to the rise of the internet and modern digital technologies, the U.S. has maintained its leadership by balancing economic incentives with strategic policy interventions.

In January 2025, President Donald Trump issued an executive order calling for the development of an AI action plan for America. My team and I have developed an AI governance model that can underpin an action plan.

Previous presidential administrations have waded into AI governance, including the Biden administration’s since-recinded executive order. There has also been an increasing number of regulations concerning AI passed at the state level. But the U.S. has mostly avoided imposing regulations on AI. This hands-off approach stems in part from a disconnect between Congress and industry, with each doubting the other’s understanding of the technologies requiring governance.

The industry is divided into distinct camps, with smaller companies allowing tech giants to lead governance discussions. Other contributing factors include ideological resistance to regulation, geopolitical concerns and insufficient coalition-building that have marked past technology policymaking efforts. Yet, our study showed that both parties in Congress favor a uniquely American approach to governance.

Congress agrees on extending American leadership, addressing AI’s infrastructure needs and focusing on specific uses of the technology – instead of trying to regulate the technology itself. How to do it? My team’s findings led us to develop the Dynamic Governance Model, a policy-agnostic and nonregulatory method that can be applied to different industries and uses of the technology. It starts with a legislative or executive body setting a policy goal and consists of three subsequent steps:

Establish a public-private partnership in which public and private sector experts work together to identify standards for evaluating the policy goal. This approach combines industry leaders’ technical expertise and innovation focus with policymakers’ agenda of protecting the public interest through oversight and accountability. By integrating these complementary roles, governance can evolve together with technological developments.

Create an ecosystem for audit and compliance mechanisms. This market-based approach builds on the standards from the previous step and executes technical audits and compliance reviews. Setting voluntary standards and measuring against them is good, but it can fall short without real oversight. Private sector auditing firms can provide oversight so long as those auditors meet fixed ethical and professional standards.

Set up accountability and liability for AI systems. This step outlines the responsibilities that a company must bear if its products harm people or fail to meet standards. Effective enforcement requires coordinated efforts across institutions. Congress can establish legislative foundations, including liability criteria and sector-specific regulations. It can also create mechanisms for ongoing oversight or rely on existing government agencies for enforcement. Courts will interpret statutes and resolve conflicts, setting precedents. Judicial rulings will clarify ambiguous areas and contribute to a sturdier framework.

I believe that this approach offers a balanced path forward, fostering public trust while allowing innovation to thrive. In contrast to conventional regulatory methods that impose blanket restrictions on industry, like the one adopted by the European Union, our model:

The U.S. has long led the world in technological growth and innovation. Pursuing a public-private partnership approach to AI governance should enable policymakers and industry leaders to advance their goals while balancing innovation with transparency and responsibility. We believe that our governance model is aligned with the Trump administration’s goal of removing barriers for industry but also supports the public’s desire for guardrails.

![]()

Carvão advises tech startups and invests in venture capital.

Big data technology can be invaluable for companies trying to improve their efficiency in 2025.

There is an enduring myth that many technological innovations have come out of garages, bedrooms and basements.

One of the most famous garages is the one at Steve Jobs’ parents’ house where he was rumoured to have designed the Apple I computer, along with Steve Wozniak and some colleagues. The myth was so persistent, that the garage was designated as a site of historical importance in 2013. It was a similar story for the founders of Google, who set up their first offices in an actual garage in Menlo Park in San Jose, Calif.

Then there was William Hewlett and David Packard, who developed a low-distortion frequency oscillator in their garage in Palo Alto, before going on to found the information technology company HP Inc. One of their first customers was Walt Disney, who used it for the sound in his 1940 film Fantasia.

The garage is an important site in the founding myths of many entrepreneurial adventures. Before a company becomes successful, where it starts out is as important as the visionaries who invest in it. And in addition to the specific space of the garage, the surrounding urban environment is also important. What a city offers, and the way it is organized, both contribute to innovation.

This article is part of our series Our cities from yesterday to tomorrow. Urban life is going through many transformations, each with cultural, economic, social – and, in this election year, political – implications. To shed light on these diverse issues, The Conversation Canada is inviting researchers to discuss the current state of our cities.

There are many spaces specifically designed to support entrepreneurship today, including incubators, accelerators and collaborative workspaces. In addition to providing a place to work, these spaces facilitate both networking with potential partners and access to business opportunities.

It is also interesting to note how these creative spaces have multiplied in most cities, sometimes with a specialization. They can be found in the fields of health, social innovation and digital technologies.

Yet, as important as they may be for some players, these spaces are not the only factors that contribute to entrepreneurial success. Other places, sometimes unexpected, such as the fast food restaurant where Nvidia was born or the Californian saunas that have replaced luxury hotels for business meetings between investors and entrepreneurs, also contribute to the creation and development of new companies. Nor can the success of an entrepreneurial venture be explained by a single place.

That raises the question: what do we know about how cities, and the variety of places within them, affect the development of entrepreneurial capacity?

As a postdoctoral researcher at HEC Montréal (MOSAIC) and a professor of innovation management at the IAE Nantes University, respectively, we have explored this question as part of our research in innovation management, particularly in a recent piece of research.

Research has long focused on specific types of places. The aim is both to understand what happens there and to extract lessons that can be replicated elsewhere. Accessing a shared workspace offers entrepreneurs the opportunity to socialize. This was also the great promise of the American company WeWork: to be a member of a community.

À lire aussi :

WeWork : chute d’une entreprise ou fin du coworking ?

Specific technologies or tools for prototyping can be found in a fab lab or a collaborative manufacturing workshop. Presenting your project to investors is easier from an incubator or accelerator. For example, by presenting a project at Y-Combinator in California, an accelerator renowned for supporting promising projects, entrepreneurs know they’ll get noticed by investors.

Similarly, it is easier to meet potential partners or pick up on the latest trends in a market or technologies by spending the evening in a trendy café or bar. Informal exchanges are easier there and these play a big role in the entrepreneurial dynamics of a territory.

And then, quite simply, where does the initial idea come from? As the American columnist and writer Steven Johnson shows through the examples of Gutenberg and Darwin, it is clear this often happens at odd times and in unusual places.

As a result, whether innovators are entrepreneurs, artists or scientists, it is unlikely that all the resources they require will be available to everyone, all the time, in one place.

As the American urban planner and sociologist Jane Jacobs so aptly put it, individuals experience the city. They do not got to a single place: they visit or pass by a variety of places, each of which, in its own way, can nurture the creativity and career of an entrepreneur. Our research reveals that it is above all the combination of a city’s places – their diversity of size, function, purpose and location – that produces entrepreneurial capacity.

Let’s take the example of creators who produce projection mapping works in Montréal. Thanks to a six-month survey of 21 Montréal artists, we were able to show the heterogeneity of places they visited regularly throughout the process of creation and development.

Thousands of subscribers already receive The Conversation’s Canada Daily newsletter. And you? Subscribe today to our newsletter to better understand today’s major issues.

_

Our study led to two main conclusions.

Firstly, depending on the profile of individuals and their creative approach, the places they visit regularly are different, and sometimes distinctive. This is the case, for example, of an artist who benefits from a residency in a printing workshop to create a projection on fabrics. It is also the case of a designer who goes to a fab lab to experiment with sensors.

This suggests that there are specific trajectories for each individual, and therefore, no single path that leads to innovation.

Secondly, this observation suggests that the convergence around certain places does not owe to chance: multiple resources, sometimes crucial for recognition in a field, are mobilized there.

For example, many of the artists in our study regularly visited Montréal’s Society for Arts and Technology (SAT), a renowned meeting place that has helped the careers of many artists. The artists we met go there to take courses, attend shows, and meet musicians with whom they may eventually collaborate.

That’s how a venue’s reputation is built. As we have shown, this can become essential at a particular stage of the entrepreneur’s journey.

But before or after this stage, other places may be more beneficial.

In fact, depending on the phase of the innovation project, the types of places visited and their number vary greatly. So, since needs are different, the capacity to innovate depends on the places and possibilities that exist in a city. For example, Montréal’s diverse cultural offerings, with its artist-run centres and performance halls, strongly inspire projection mapping artists.

Workshops are obviously important places for experimentation and creation, but they are only used when a prototype or final work is being produced.

In a more global context, where there are many technological, societal and environmental challenges, innovations are necessary.

Ideas and entrepreneurs are essential to make innovation happen. Entrepreneurs need skills and financial resources. They need to be part of collectives and communities. But also, and perhaps even above all, they need to be in territories that offer a wide range of places where they can take advantage of complementary resources to carry out their projects.

The city as a whole, and on a smaller scale, its neighbourhoods, are the melting pot from which ideas circulate and mix, where projects mature and take shape. The urban morphology, which can be seen as a particular arrangement of places and transport or travel infrastructures, then becomes a new deciding factor in entrepreneurial capacity.

![]()

Les auteurs ne travaillent pas, ne conseillent pas, ne possèdent pas de parts, ne reçoivent pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'ont déclaré aucune autre affiliation que leur organisme de recherche.