Prototypes for Humanity showcases solutions-based projects from universities around the world – in Dubai

Flash cars, flashier skyscrapers, strict public behaviour laws and soaring temperatures. Social media, reality television shows and news reports on expat extravagances and holidays gone wrong ensure that Dubai has many images. Being a hub for international research probably isn’t one that springs to most people’s minds.

That may be about to change though. A number of leading international institutions have established bases in the United Arab Emirates in recent years, including the University of Birmingham, a founder member of The Conversation UK, which has a campus in Dubai.

And for more than a decade now the city has provided a showcase for international design and innovation research in the form of a project that began life as essentially a degree show but that is now morphing into a community of PhD candidates and their professors seeking to take ideas that can deliver tangible benefits to cities, the planet and human health out of the lab and into the marketplace.

Prototypes for Humanity, part of Dubai Future Solutions, presented 100 projects offering tangible ways to tackle key challenges facing societies. More than 2,700 entries were submitted from 800 universities around the world. Many of those researchers chosen to exhibit at the Emirates Towers event from November 19-22 came The Conversation’s member institutions.

One of the first of those that caught my eye was a system, under development by Alexander Burton at RMIT in Melbourne, Australia, to retrofit petrol vehicles so they can operate as hybrids. Given the apparent complexities of production line hybrid cars it struck me as outlandish. But showing me his display and some of the kit, Alexander explained how he and his dad had come up with the concept of transforming their Toyota.

The team hope that retro-fit hybrids will take off in rural and suburban areas and could find an export market. The model, says Alexander, particularly lends itself to pick-up trucks where there’s plenty of space to bolt on the supplementary electrical units and they can offer significant savings.

Just a few feet away was another electric vehicle innovation, this time from the University of Southampton in southern England. Tamara Ivancova has developed what is being described as a “four-wheeled e-bike” – think, enclosed narrow car that can run in a cycle lane. Tamara has used experience gained working in Forumla 1 (from the age of 15) and at university to develop specialist recycled materials and a full scale mock up of the product is in a garage in Southampton.

Alongside projects developing new materials and energy innovations, data, agriculture, environment and health were key themes among the 100 selected to exhibit. I should add that my own travel and accommodation was provided by Prototypes.

In one of the adjacent offices, Tadeu Baldani Caravieri, Director of Prototypes for Humanity, elaborated on the team’s vision of the project “as the world’s most comprehensive convener of academic innovation”.

“The diversity, depth and range of applications received – covering all fields of sciences, technology and creative studies – make the initiative reflect the current global state of innovation and how complex global issues are manifested, and addressed, by top academic talent.

“Together, we’re raising awareness of academia’s essential role in driving progress and collaboratively developing solutions that create tangible impacts on people’s lives.”

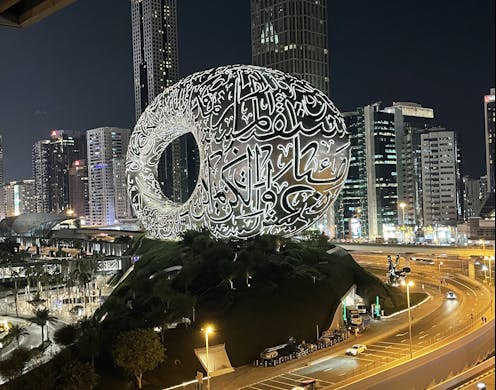

Led by the Art Dubai Group, the Prototypes for Humanity initiative is supported by the government of Dubai and seeks to place the city at the heart of such academic research-driven solutions.

For the first time, this year’s exhibition also provided an opportunity for five projects’s students and professors to secure a share of US$100,000 in investment funding. Among those was Bill Yen, a PhD candidate at Stanford University in California who has developed a fuel cell that generates renewable energy from microbes breaking down organic carbon in soil.

Another securing investment was Xinpeng Hong, a final year PhD candidate at the University of Oxford, for a machine learning project that speeds up computation and lowers energy use required for such technology. The work has potential applications in healthcare, transport and finance sectors.

For The Conversation, it was an introduction to some projects that I expect you’ll hear and read more about in our content in the months to come. While we rightly assess and explain events as they happen, delivering information about new research, and particularly innovative solutions that are born in the labs, studios and seminars of our partner universities is also a central element of our mission as we strive to be the comprehensive conveyor of academic knowledge.

![]()