How to Recover Data from an Unreadable External Hard Drive

Data-driven businesses need to make hard drive data recovery options part of their data loss strategy.

Data-driven businesses need to make hard drive data recovery options part of their data loss strategy.

You want to choose the right program if you want to get a data science degree.

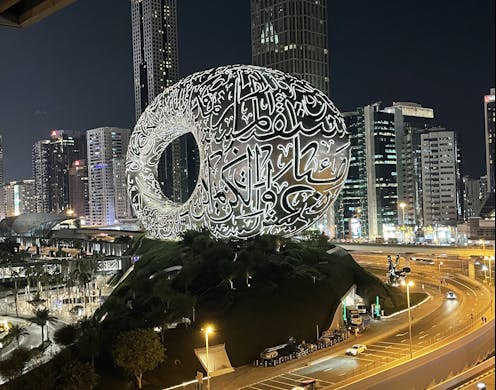

Flash cars, flashier skyscrapers, strict public behaviour laws and soaring temperatures. Social media, reality television shows and news reports on expat extravagances and holidays gone wrong ensure that Dubai has many images. Being a hub for international research probably isn’t one that springs to most people’s minds.

That may be about to change though. A number of leading international institutions have established bases in the United Arab Emirates in recent years, including the University of Birmingham, a founder member of The Conversation UK, which has a campus in Dubai.

And for more than a decade now the city has provided a showcase for international design and innovation research in the form of a project that began life as essentially a degree show but that is now morphing into a community of PhD candidates and their professors seeking to take ideas that can deliver tangible benefits to cities, the planet and human health out of the lab and into the marketplace.

Prototypes for Humanity, part of Dubai Future Solutions, presented 100 projects offering tangible ways to tackle key challenges facing societies. More than 2,700 entries were submitted from 800 universities around the world. Many of those researchers chosen to exhibit at the Emirates Towers event from November 19-22 came The Conversation’s member institutions.

One of the first of those that caught my eye was a system, under development by Alexander Burton at RMIT in Melbourne, Australia, to retrofit petrol vehicles so they can operate as hybrids. Given the apparent complexities of production line hybrid cars it struck me as outlandish. But showing me his display and some of the kit, Alexander explained how he and his dad had come up with the concept of transforming their Toyota.

The team hope that retro-fit hybrids will take off in rural and suburban areas and could find an export market. The model, says Alexander, particularly lends itself to pick-up trucks where there’s plenty of space to bolt on the supplementary electrical units and they can offer significant savings.

Just a few feet away was another electric vehicle innovation, this time from the University of Southampton in southern England. Tamara Ivancova has developed what is being described as a “four-wheeled e-bike” – think, enclosed narrow car that can run in a cycle lane. Tamara has used experience gained working in Forumla 1 (from the age of 15) and at university to develop specialist recycled materials and a full scale mock up of the product is in a garage in Southampton.

Alongside projects developing new materials and energy innovations, data, agriculture, environment and health were key themes among the 100 selected to exhibit. I should add that my own travel and accommodation was provided by Prototypes.

In one of the adjacent offices, Tadeu Baldani Caravieri, Director of Prototypes for Humanity, elaborated on the team’s vision of the project “as the world’s most comprehensive convener of academic innovation”.

“The diversity, depth and range of applications received – covering all fields of sciences, technology and creative studies – make the initiative reflect the current global state of innovation and how complex global issues are manifested, and addressed, by top academic talent.

“Together, we’re raising awareness of academia’s essential role in driving progress and collaboratively developing solutions that create tangible impacts on people’s lives.”

Led by the Art Dubai Group, the Prototypes for Humanity initiative is supported by the government of Dubai and seeks to place the city at the heart of such academic research-driven solutions.

For the first time, this year’s exhibition also provided an opportunity for five projects’s students and professors to secure a share of US$100,000 in investment funding. Among those was Bill Yen, a PhD candidate at Stanford University in California who has developed a fuel cell that generates renewable energy from microbes breaking down organic carbon in soil.

Another securing investment was Xinpeng Hong, a final year PhD candidate at the University of Oxford, for a machine learning project that speeds up computation and lowers energy use required for such technology. The work has potential applications in healthcare, transport and finance sectors.

For The Conversation, it was an introduction to some projects that I expect you’ll hear and read more about in our content in the months to come. While we rightly assess and explain events as they happen, delivering information about new research, and particularly innovative solutions that are born in the labs, studios and seminars of our partner universities is also a central element of our mission as we strive to be the comprehensive conveyor of academic knowledge.

![]()

Flash cars, flashier skyscrapers, strict public behaviour laws and soaring temperatures. Social media, reality television shows and news reports on expat extravagances and holidays gone wrong ensure that Dubai has many images. Being a hub for international research probably isn’t one that springs to most people’s minds.

That may be about to change though. A number of leading international institutions have established bases in the United Arab Emirates in recent years, including the University of Birmingham, a founder member of The Conversation UK, which has a campus in Dubai.

And for more than a decade now the city has provided a showcase for international design and innovation research in the form of a project that began life as essentially a degree show but that is now morphing into a community of PhD candidates and their professors seeking to take ideas that can deliver tangible benefits to cities, the planet and human health out of the lab and into the marketplace.

Prototypes for Humanity, part of Dubai Future Solutions, presented 100 projects offering tangible ways to tackle key challenges facing societies. More than 2,700 entries were submitted from 800 universities around the world. Many of those researchers chosen to exhibit at the Emirates Towers event from November 19-22 came The Conversation’s member institutions.

One of the first of those that caught my eye was a system, under development by Alexander Burton at RMIT in Melbourne, Australia, to retrofit petrol vehicles so they can operate as hybrids. Given the apparent complexities of production line hybrid cars it struck me as outlandish. But showing me his display and some of the kit, Alexander explained how he and his dad had come up with the concept of transforming their Toyota.

The team hope that retro-fit hybrids will take off in rural and suburban areas and could find an export market. The model, says Alexander, particularly lends itself to pick-up trucks where there’s plenty of space to bolt on the supplementary electrical units and they can offer significant savings.

Just a few feet away was another electric vehicle innovation, this time from the University of Southampton in southern England. Tamara Ivancova has developed what is being described as a “four-wheeled e-bike” – think, enclosed narrow car that can run in a cycle lane. Tamara has used experience gained working in Forumla 1 (from the age of 15) and at university to develop specialist recycled materials and a full scale mock up of the product is in a garage in Southampton.

Alongside projects developing new materials and energy innovations, data, agriculture, environment and health were key themes among the 100 selected to exhibit. I should add that my own travel and accommodation was provided by Prototypes.

In one of the adjacent offices, Tadeu Baldani Caravieri, Director of Prototypes for Humanity, elaborated on the team’s vision of the project “as the world’s most comprehensive convener of academic innovation”.

“The diversity, depth and range of applications received – covering all fields of sciences, technology and creative studies – make the initiative reflect the current global state of innovation and how complex global issues are manifested, and addressed, by top academic talent.

“Together, we’re raising awareness of academia’s essential role in driving progress and collaboratively developing solutions that create tangible impacts on people’s lives.”

Led by the Art Dubai Group, the Prototypes for Humanity initiative is supported by the government of Dubai and seeks to place the city at the heart of such academic research-driven solutions.

For the first time, this year’s exhibition also provided an opportunity for five projects’s students and professors to secure a share of US$100,000 in investment funding. Among those was Bill Yen, a PhD candidate at Stanford University in California who has developed a fuel cell that generates renewable energy from microbes breaking down organic carbon in soil.

Another securing investment was Xinpeng Hong, a final year PhD candidate at the University of Oxford, for a machine learning project that speeds up computation and lowers energy use required for such technology. The work has potential applications in healthcare, transport and finance sectors.

For The Conversation, it was an introduction to some projects that I expect you’ll hear and read more about in our content in the months to come. While we rightly assess and explain events as they happen, delivering information about new research, and particularly innovative solutions that are born in the labs, studios and seminars of our partner universities is also a central element of our mission as we strive to be the comprehensive conveyor of academic knowledge.

![]()

There’s been an exciting new discovery in the fight against plastic pollution: mealworm larvae that are capable of consuming polystyrene. They join the ranks of a small group of insects that have been found to be capable of breaking the polluting plastic down, though this is the first time that an insect species native to Africa has been found to do this.

Polystyrene, commonly known as styrofoam, is a plastic material that’s widely used in food, electronic and industrial packaging. It’s difficult to break down and therefore durable. Traditional recycling methods – like chemical and thermal processing – are expensive and can create pollutants. This was one of the reasons we wanted to explore biological methods of managing this persistent waste.

I am part of a team of scientists from the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology who have found that the larvae of the Kenyan lesser mealworm can chew through polystyrene and host bacteria in their guts that help break down the material.

The lesser mealworm is the larval form of the Alphitobius darkling beetle. The larval period lasts between 8 and 10 weeks. The lesser mealworm are mostly found in poultry rearing houses which are warm and can offer a constant food supply – ideal conditions for them to grow and reproduce.

Though lesser mealworms are thought to have originated in Africa, they can be found in many countries around the world. The species we identified in our study, however, could be a sub-species of the Alphitobius genus. We are conducting further investigation to confirm this possibility.

Our study also examined the insect’s gut bacteria. We wanted to identify the bacterial communities that may support the plastic degradation process.

Plastic pollution levels are at critically high levels in some African countries. Though plastic waste is a major environmental issue globally, Africa faces a particular challenge due to high importation of plastic products, low re-use and a lack of recycling of these products.

By studying these natural “plastic-eaters”, we hope to create new tools that help get rid of plastic waste faster and more efficiently. Instead of releasing a huge number of these insects into trash sites (which isn’t practical), we can use the microbes and enzymes they produce in factories, landfills and cleanup sites. This means plastic waste can be tackled in a way that’s easier to manage at a large scale.

We carried out a trial, lasting over a month. The larvae were fed either polystyrene alone, bran (a nutrient-dense food) alone, or a combination of polystyrene and bran.

We found that mealworms on the polystyrene-bran diet survived at higher rates than those fed on polystyrene alone. We also found that they consumed polystyrene more efficiently than those on a polystyrene-only diet. This highlights the benefits of ensuring the insects still had a nutrient-dense diet.

While the polystyrene-only diet did support the mealworms’ survival, they didn’t have enough nutrition to make them efficient in breaking down polystyrene. This finding reinforced the importance of a balanced diet for the insects to optimally consume and degrade plastic. The insects could be eating the polystyrene because it’s mostly made up of carbon and hydrogen, which may provide them an energy source.

The mealworms on the polystyrene-bran diet were able to break down approximately 11.7% of the total polystyrene over the trial period.

The analysis of the mealworm gut revealed significant shifts in the bacterial composition depending on the diet. Understanding these shifts in bacterial composition is crucial because it reveals which microbes are actively involved in breaking down plastic. This will help us to isolate the specific bacteria and enzymes that can be harnessed for plastic degradation efforts.

The guts of polystyrene-fed larvae were found to contain higher levels of Proteobacteria and Firmicutes, bacteria that can adapt to various environments and break down a wide range of complex substances. Bacteria such as Kluyvera, Lactococcus, Citrobacter and Klebsiella were also particularly abundant and are known to produce enzymes capable of digesting synthetic plastics. The bacteria won’t be harmful to the insect or to the environment when used at scale.

The abundance of bacteria indicates that they play a crucial role in breaking down the plastic. This may mean that mealworms may not naturally have the ability to eat plastic. Instead, when they start eating plastic, the bacteria in their guts might change to help break it down. Thus, the microbes in the mealworms’ stomachs can adjust to unusual diets, like plastic.

These findings support our hypothesis that the gut of certain insects can enable plastic degradation. This is likely because the bacteria in their gut can produce enzymes that break down plastic polymers.

This raises the possibility of isolating these bacteria, and the enzymes produced, to create microbial solutions that will address plastic waste on a larger scale.

Certain insect species, such as yellow mealworms (Tenebrio molitor) and superworms (Zophobas morio), have already demonstrated the ability to consume plastics. They’re able to break down materials like polystyrene with the help of bacteria in their gut.

Our research is unique because it focuses on insect species native to Africa, which have not been extensively studied in the context of plastic degradation.

This regional focus is important because the insects and environmental conditions in Africa may differ from those in other parts of the world, potentially offering new insights and practical solutions for plastic pollution in African settings.

The Kenyan lesser mealworm’s ability to consume polystyrene suggests that it could play a role in natural waste reduction, especially for types of plastic that are resistant to conventional recycling methods.

Future studies could focus on isolating and identifying the specific bacterial strains involved in polystyrene degradation and examining their enzymes.

We hope to figure out if the enzymes can be produced at scale for recycling waste.

Additionally, we may explore other types of plastics to test the versatility of this insect for broader waste management applications.

Scaling up the use of the lesser mealworms for plastic degradation would also require strategies for ensuring insect health over prolonged plastic consumption, as well as evaluating the safety of resulting insect biomass for animal feeds.

![]()

This research was funded by: Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research, Novo nordisk fonden (Refugee Insect Production for Food and Feed (RefIPro), the Rockefeller Foundation; Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; IKEA Foundation; European Commission, the Curt Bergfors Foundation Food Planet Prize Award; Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation, Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida); Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC); Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR); Government of Norway; German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ); and Government of the Republic of Kenya. The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the donors.

There’s been an exciting new discovery in the fight against plastic pollution: mealworm larvae that are capable of consuming polystyrene. They join the ranks of a small group of insects that have been found to be capable of breaking the polluting plastic down, though this is the first time that an insect species native to Africa has been found to do this.

Polystyrene, commonly known as styrofoam, is a plastic material that’s widely used in food, electronic and industrial packaging. It’s difficult to break down and therefore durable. Traditional recycling methods – like chemical and thermal processing – are expensive and can create pollutants. This was one of the reasons we wanted to explore biological methods of managing this persistent waste.

I am part of a team of scientists from the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology who have found that the larvae of the Kenyan lesser mealworm can chew through polystyrene and host bacteria in their guts that help break down the material.

The lesser mealworm is the larval form of the Alphitobius darkling beetle. The larval period lasts between 8 and 10 weeks. The lesser mealworm are mostly found in poultry rearing houses which are warm and can offer a constant food supply – ideal conditions for them to grow and reproduce.

Though lesser mealworms are thought to have originated in Africa, they can be found in many countries around the world. The species we identified in our study, however, could be a sub-species of the Alphitobius genus. We are conducting further investigation to confirm this possibility.

Our study also examined the insect’s gut bacteria. We wanted to identify the bacterial communities that may support the plastic degradation process.

Plastic pollution levels are at critically high levels in some African countries. Though plastic waste is a major environmental issue globally, Africa faces a particular challenge due to high importation of plastic products, low re-use and a lack of recycling of these products.

By studying these natural “plastic-eaters”, we hope to create new tools that help get rid of plastic waste faster and more efficiently. Instead of releasing a huge number of these insects into trash sites (which isn’t practical), we can use the microbes and enzymes they produce in factories, landfills and cleanup sites. This means plastic waste can be tackled in a way that’s easier to manage at a large scale.

We carried out a trial, lasting over a month. The larvae were fed either polystyrene alone, bran (a nutrient-dense food) alone, or a combination of polystyrene and bran.

We found that mealworms on the polystyrene-bran diet survived at higher rates than those fed on polystyrene alone. We also found that they consumed polystyrene more efficiently than those on a polystyrene-only diet. This highlights the benefits of ensuring the insects still had a nutrient-dense diet.

While the polystyrene-only diet did support the mealworms’ survival, they didn’t have enough nutrition to make them efficient in breaking down polystyrene. This finding reinforced the importance of a balanced diet for the insects to optimally consume and degrade plastic. The insects could be eating the polystyrene because it’s mostly made up of carbon and hydrogen, which may provide them an energy source.

The mealworms on the polystyrene-bran diet were able to break down approximately 11.7% of the total polystyrene over the trial period.

The analysis of the mealworm gut revealed significant shifts in the bacterial composition depending on the diet. Understanding these shifts in bacterial composition is crucial because it reveals which microbes are actively involved in breaking down plastic. This will help us to isolate the specific bacteria and enzymes that can be harnessed for plastic degradation efforts.

The guts of polystyrene-fed larvae were found to contain higher levels of Proteobacteria and Firmicutes, bacteria that can adapt to various environments and break down a wide range of complex substances. Bacteria such as Kluyvera, Lactococcus, Citrobacter and Klebsiella were also particularly abundant and are known to produce enzymes capable of digesting synthetic plastics. The bacteria won’t be harmful to the insect or to the environment when used at scale.

The abundance of bacteria indicates that they play a crucial role in breaking down the plastic. This may mean that mealworms may not naturally have the ability to eat plastic. Instead, when they start eating plastic, the bacteria in their guts might change to help break it down. Thus, the microbes in the mealworms’ stomachs can adjust to unusual diets, like plastic.

These findings support our hypothesis that the gut of certain insects can enable plastic degradation. This is likely because the bacteria in their gut can produce enzymes that break down plastic polymers.

This raises the possibility of isolating these bacteria, and the enzymes produced, to create microbial solutions that will address plastic waste on a larger scale.

Certain insect species, such as yellow mealworms (Tenebrio molitor) and superworms (Zophobas morio), have already demonstrated the ability to consume plastics. They’re able to break down materials like polystyrene with the help of bacteria in their gut.

Our research is unique because it focuses on insect species native to Africa, which have not been extensively studied in the context of plastic degradation.

This regional focus is important because the insects and environmental conditions in Africa may differ from those in other parts of the world, potentially offering new insights and practical solutions for plastic pollution in African settings.

The Kenyan lesser mealworm’s ability to consume polystyrene suggests that it could play a role in natural waste reduction, especially for types of plastic that are resistant to conventional recycling methods.

Future studies could focus on isolating and identifying the specific bacterial strains involved in polystyrene degradation and examining their enzymes.

We hope to figure out if the enzymes can be produced at scale for recycling waste.

Additionally, we may explore other types of plastics to test the versatility of this insect for broader waste management applications.

Scaling up the use of the lesser mealworms for plastic degradation would also require strategies for ensuring insect health over prolonged plastic consumption, as well as evaluating the safety of resulting insect biomass for animal feeds.

![]()

This research was funded by: Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research, Novo nordisk fonden (Refugee Insect Production for Food and Feed (RefIPro), the Rockefeller Foundation; Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; IKEA Foundation; European Commission, the Curt Bergfors Foundation Food Planet Prize Award; Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation, Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida); Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC); Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR); Government of Norway; German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ); and Government of the Republic of Kenya. The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the donors.

The US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is often held as a model for driving technology advances. For decades, it has contributed to military and economic dominance by bridging the gap between military and civilian applications. European policymakers frequently reference DARPA in discussions, as outlined in the 2024 Draghi Report, but an EU equivalent has yet to materialise. To create such an agency, the governance and management of European innovation programmes would need drastic changes.

Founded in 1958, DARPA operates under the US Department of Defense (DoD) with a straightforward mission: to fund high-risk technological programmes that could lead to radical innovation. DARPA provides support throughout the innovation process, focusing on environments where new uses for technology must be invented or adapted. Although part of the DoD, DARPA funds projects that promise technological and economic superiority whether they align with current military priorities or not. DARPA has backed projects like ARPANET, the precursor to the internet, and the GPS. Today, DARPA shows interest in autonomous vehicles for urban areas and new missile technologies.

As part of its core mission, DARPA accepts high financial risks on exploration projects and makes long-term commitments to these projects. Many emblematic successes explain why DARPA is a reference agency. However, the list of failed projects is even longer. Both failures and successes feed the exploration process in emerging industrial sectors. They represent opportunities to learn together and build collective strategies in innovation ecosystems.

DARPA’s success stems not just from its stability but from adhering to five organisational principles that allow it to explore deep tech in an open innovation context:

Independence: DARPA operates independently from other military services, research & development centres and federal agencies, allowing it to explore options outside dominant research paradigms. While cooperation is possible, its decisions and directions are not influenced by other parts of the federal administration.

Agility: The agency’s flat organisational structure minimises bureaucracy. Its independent decision-making processes and streamlined contracting allow it to pivot quickly, test new concepts and collaborate with academic or private sector partners. Agility also enables DARPA to test new exploration or experimentation methods that are often based on user-centric approaches. Potential military or civilian end-users are involved very early in innovation projects to discuss potential uses and applications. This approach has recently led DARPA to absorb the Strategic Capabilities Office (SCO), where officers from the different military services (Army, Air Force, Navy and Marines) and all military ranks test new technological solutions (from different maturity levels), fostering co-creation processes with military innovators and expanding the agency’s impact.

Sponsorship: High-ranking executives within the DoD and other federal administrations (NASA, Department of Energy) endorse, but do not commission, DARPA’s projects. This sponsorship model increases a project’s potential impact and allows for swift adaptation if a project fails.

Community building: DARPA creates innovation communities with a mix of diverse expertise. By bringing different perspectives together, it fosters collective strategies essential for disruptive innovation.

Diverse leadership: Project managers come from a range of backgrounds, including civilian experts, military officers and private-sector professionals. All have demonstrated scientific and technological expertise and a solid capability to bridge dreams and foresight with reality. All have a perfect command of risk and complexity management. Managers serve three- to four-year terms focused on driving technological disruption and building new innovation ecosystems. Their diverse expertise sets DARPA apart from other federal agencies.

The Draghi Report on European competitiveness suggests that a European DARPA could help bridge technological gaps, reduce dependencies and accelerate the green transition. However, implementing this model would require a seismic shift in how European agencies operate. Creating a new agency would be ineffective without ensuring that all principles underlying the success of DARPA are implemented in Europe.

Even if Europe actively promotes deep tech and devotes significant budgets to it, European public policies and ways of working prevailing in national and European agencies are hardly consistent with the DARPA model. European agencies do not have much autonomy in their decisions about the exploration of new ventures or human resource management. They clearly demonstrate an outcome-focused orientation inconsistent with DARPA’s approach to risk.

European agencies often lack the stable missions, scope and ambition seen at DARPA. The European Space Agency (ESA), the European Defence Agency (EDA) and Eurocontrol highlight the difficulties in developing cohesive, cross-border innovation ecosystems. A European DARPA would require a unified ambition among EU member states, a challenging feat given the institutional and geopolitical divides within Europe. The debates around the European Defence Fund illustrate how complex it is to reach consensus on shared objectives and funding.

Adopting DARPA’s five organisational principles would represent a cultural revolution for European agencies in relation to EU bureaucratic norms and the budgetary controls of individual member states. Implementing these changes would also disrupt the existing power balance between countries. The DARPA model is inconsistent with the European “fair returns” model that refers to proportionality rules between funding, research operations and then industrial repartition during the production phase between member states in each project. The DARPA model would only focus on existing competencies, excellence, risk-taking approaches and entrepreneurial mindsets.

Establishing a European DARPA would require a fundamental rethinking of public policy management in Europe. Its success would depend on whether European stakeholders are willing to adopt DARPA’s core principles, including its independence, agility and willingness to accept failure. Creating an agency is one thing; ensuring it adheres to the structures that make DARPA effective is another. The question remains: Is Europe ready for this transformation?

The European Academy of Management (EURAM) is a learned society founded in 2001. With over 2,000 members from 60 countries in Europe and beyond, EURAM aims at advancing the academic discipline of management in Europe.

![]()

David W. Versailles has received funding from the French Ministry of Defence to develop this research.

Valérie Mérindol has received funding from the French Ministry of the Armed Forces to develop this research.

The US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is often held as a model for driving technology advances. For decades, it has contributed to military and economic dominance by bridging the gap between military and civilian applications. European policymakers frequently reference DARPA in discussions, as outlined in the 2024 Draghi Report, but an EU equivalent has yet to materialise. To create such an agency, the governance and management of European innovation programmes would need drastic changes.

Founded in 1958, DARPA operates under the US Department of Defense (DoD) with a straightforward mission: to fund high-risk technological programmes that could lead to radical innovation. DARPA provides support throughout the innovation process, focusing on environments where new uses for technology must be invented or adapted. Although part of the DoD, DARPA funds projects that promise technological and economic superiority whether they align with current military priorities or not. DARPA has backed projects like ARPANET, the precursor to the internet, and the GPS. Today, DARPA shows interest in autonomous vehicles for urban areas and new missile technologies.

As part of its core mission, DARPA accepts high financial risks on exploration projects and makes long-term commitments to these projects. Many emblematic successes explain why DARPA is a reference agency. However, the list of failed projects is even longer. Both failures and successes feed the exploration process in emerging industrial sectors. They represent opportunities to learn together and build collective strategies in innovation ecosystems.

DARPA’s success stems not just from its stability but from adhering to five organisational principles that allow it to explore deep tech in an open innovation context:

Independence: DARPA operates independently from other military services, research & development centres and federal agencies, allowing it to explore options outside dominant research paradigms. While cooperation is possible, its decisions and directions are not influenced by other parts of the federal administration.

Agility: The agency’s flat organisational structure minimises bureaucracy. Its independent decision-making processes and streamlined contracting allow it to pivot quickly, test new concepts and collaborate with academic or private sector partners. Agility also enables DARPA to test new exploration or experimentation methods that are often based on user-centric approaches. Potential military or civilian end-users are involved very early in innovation projects to discuss potential uses and applications. This approach has recently led DARPA to absorb the Strategic Capabilities Office (SCO), where officers from the different military services (Army, Air Force, Navy and Marines) and all military ranks test new technological solutions (from different maturity levels), fostering co-creation processes with military innovators and expanding the agency’s impact.

Sponsorship: High-ranking executives within the DoD and other federal administrations (NASA, Department of Energy) endorse, but do not commission, DARPA’s projects. This sponsorship model increases a project’s potential impact and allows for swift adaptation if a project fails.

Community building: DARPA creates innovation communities with a mix of diverse expertise. By bringing different perspectives together, it fosters collective strategies essential for disruptive innovation.

Diverse leadership: Project managers come from a range of backgrounds, including civilian experts, military officers and private-sector professionals. All have demonstrated scientific and technological expertise and a solid capability to bridge dreams and foresight with reality. All have a perfect command of risk and complexity management. Managers serve three- to four-year terms focused on driving technological disruption and building new innovation ecosystems. Their diverse expertise sets DARPA apart from other federal agencies.

The Draghi Report on European competitiveness suggests that a European DARPA could help bridge technological gaps, reduce dependencies and accelerate the green transition. However, implementing this model would require a seismic shift in how European agencies operate. Creating a new agency would be ineffective without ensuring that all principles underlying the success of DARPA are implemented in Europe.

Even if Europe actively promotes deep tech and devotes significant budgets to it, European public policies and ways of working prevailing in national and European agencies are hardly consistent with the DARPA model. European agencies do not have much autonomy in their decisions about the exploration of new ventures or human resource management. They clearly demonstrate an outcome-focused orientation inconsistent with DARPA’s approach to risk.

European agencies often lack the stable missions, scope and ambition seen at DARPA. The European Space Agency (ESA), the European Defence Agency (EDA) and Eurocontrol highlight the difficulties in developing cohesive, cross-border innovation ecosystems. A European DARPA would require a unified ambition among EU member states, a challenging feat given the institutional and geopolitical divides within Europe. The debates around the European Defence Fund illustrate how complex it is to reach consensus on shared objectives and funding.

Adopting DARPA’s five organisational principles would represent a cultural revolution for European agencies in relation to EU bureaucratic norms and the budgetary controls of individual member states. Implementing these changes would also disrupt the existing power balance between countries. The DARPA model is inconsistent with the European “fair returns” model that refers to proportionality rules between funding, research operations and then industrial repartition during the production phase between member states in each project. The DARPA model would only focus on existing competencies, excellence, risk-taking approaches and entrepreneurial mindsets.

Establishing a European DARPA would require a fundamental rethinking of public policy management in Europe. Its success would depend on whether European stakeholders are willing to adopt DARPA’s core principles, including its independence, agility and willingness to accept failure. Creating an agency is one thing; ensuring it adheres to the structures that make DARPA effective is another. The question remains: Is Europe ready for this transformation?

The European Academy of Management (EURAM) is a learned society founded in 2001. With over 2,000 members from 60 countries in Europe and beyond, EURAM aims at advancing the academic discipline of management in Europe.

![]()

David W. Versailles has received funding from the French Ministry of Defence to develop this research.

Valérie Mérindol has received funding from the French Ministry of the Armed Forces to develop this research.

For its recent Spring/Summer 2025 show, fashion brand Diesel filled a runway with mounds of denim offcuts, making a spectacle of its efforts to reduce waste.

Haunting yet poetic, the “forgotten” byproducts of fashion production were reclaimed and repurposed into something artful. But the irony isn’t lost, given fashion shows like this one demand significant resources.

Diesel’s event is an example of a growing trend towards the “spectacle of sustainability”, wherein performative displays are prioritised over the deeper, structural changes needed to address environmental issues.

Can the fashion industry reconcile its tendency towards spectacle with its environmental responsibilities? The recent spacesuit collaboration between Prada and Axiom Space is one refreshing example of how it can, by leaning into innovation that seeks to advance fashion technology and rewrite fashion norms.

The fashion industry has always relied on some form of spectacle to continue the fashion cycle. Fashion shows mix art, performance and design to create powerful experiences that will grab people’s attention and set the tone for what’s “in”. Promotional material from these shows is shared widely, helping cement new trends.

However, the spectacle of fashion isn’t helpful for communicating the complexity of sustainability. Fashion events tend to focus on surface-level ideas, while ignoring deeper systemic problems such as the popularity of fast fashion, people’s buying habits, and working conditions in garment factories. These problems are connected, so addressing one requires addressing the others.

It’s much easier to host a flashy event that inevitably feeds the problem it purports to fix. International fashion events have a large carbon footprint. This is partly due to how many people they move around the world, as well as their promotion of consumption (whereas sustainability requires buying less).

The pandemic helped deliver some solutions to this problem by forcing fashion shows to go digital. Brands such as Balenciaga, the Congolese brand Hanifa and many more took part in virtual fashion shows with animated avatars – and many pointed to this as a possible solution to the industry’s sustainability issue.

But the industry has now largely returned to live fashion shows. Virtual presentations have been relegated to their own sectors within fashion communication, while live events take centre stage.

Technology and innovation clearly have a role to play in helping make fashion more sustainable. The recent Prada-Axiom spacesuit collaboration brings this into focus in a new way.

The AxEMU (Axiom Extravehicular Mobility Unit) suits will be worn by Artemis III crew members during NASA’s planned 2026 mission to the Moon. The suits have been made using long-lasting and high-performance materials that are designed to withstand the extreme conditions of space.

By joining this collaboration, Prada, known for its high fashion, is shifting into a highly symbolic arena of technological advancement. This will likely help position it at the forefront of sustainability and technology discussions – at least in the minds of consumers.

Prada itself has varying levels of compliance when it comes to meeting sustainability goals. The Standard Ethics Ratings has listed it as “sustainable”, while sustainability scoring site Good on You rated it as “not good enough” – citing a need for improved transparency and better hazardous chemical use.

Recently, the brand has been working on making recycled textiles such as nylon fabrics (nylon is a part of the brand DNA) from fishing nets and plastic bottles. It also launched a high-fashion jewellery line made of recycled gold.

Prada’s partnership with Axiom signifies a milestone in fashion’s ability to impact on high-tech industries. Beyond boosting Prada’s image, such innovations can also lead to more sustainable fashions.

For instance, advanced materials created for spacesuits could eventually be adapted into everyday heat-resistant clothing. This will become increasingly important in the context of climate change, especially in regions already struggling with drought and heatwaves. The IPCC warns that if global temperatures rise by 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, twice as many mega-cities are likely to become heat-stressed.

New innovations are trying to help consumers stay cool despite rising temperatures. Nike’s Aerogami is a performance apparel technology that supposedly increases breathability. Researchers from MIT have also designed garment vents that open and close when they sense sweat to create airflow.

Similarly, researchers from Zhengzhou University and the University of South Australia have created a fabric that reflects sunlight and releases heat to help reduce body temperatures. These kinds of cooling textiles (which could also be used in architecture) could help reduce the need for air conditioning.

One future challenge lies in driving demand for these innovations by making them seem fashionable and “cool”. Collaborations like the one between Prada and Axiom are helpful on this front. A space suit – an item typically seen as a functional, long-lasting piece of engineering – becomes something more with Prada’s name on it.

The collaboration also points to a broader potential for brands to use large attention-grabbing projects to convey their sustainability credentials. In this way they can combine spectacle with sustainability. The key will be in making sure one doesn’t come at the expense of the other.

![]()

Alyssa Choat does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

For its recent Spring/Summer 2025 show, fashion brand Diesel filled a runway with mounds of denim offcuts, making a spectacle of its efforts to reduce waste.

Haunting yet poetic, the “forgotten” byproducts of fashion production were reclaimed and repurposed into something artful. But the irony isn’t lost, given fashion shows like this one demand significant resources.

Diesel’s event is an example of a growing trend towards the “spectacle of sustainability”, wherein performative displays are prioritised over the deeper, structural changes needed to address environmental issues.

Can the fashion industry reconcile its tendency towards spectacle with its environmental responsibilities? The recent spacesuit collaboration between Prada and Axiom Space is one refreshing example of how it can, by leaning into innovation that seeks to advance fashion technology and rewrite fashion norms.

The fashion industry has always relied on some form of spectacle to continue the fashion cycle. Fashion shows mix art, performance and design to create powerful experiences that will grab people’s attention and set the tone for what’s “in”. Promotional material from these shows is shared widely, helping cement new trends.

However, the spectacle of fashion isn’t helpful for communicating the complexity of sustainability. Fashion events tend to focus on surface-level ideas, while ignoring deeper systemic problems such as the popularity of fast fashion, people’s buying habits, and working conditions in garment factories. These problems are connected, so addressing one requires addressing the others.

It’s much easier to host a flashy event that inevitably feeds the problem it purports to fix. International fashion events have a large carbon footprint. This is partly due to how many people they move around the world, as well as their promotion of consumption (whereas sustainability requires buying less).

The pandemic helped deliver some solutions to this problem by forcing fashion shows to go digital. Brands such as Balenciaga, the Congolese brand Hanifa and many more took part in virtual fashion shows with animated avatars – and many pointed to this as a possible solution to the industry’s sustainability issue.

But the industry has now largely returned to live fashion shows. Virtual presentations have been relegated to their own sectors within fashion communication, while live events take centre stage.

Technology and innovation clearly have a role to play in helping make fashion more sustainable. The recent Prada-Axiom spacesuit collaboration brings this into focus in a new way.

The AxEMU (Axiom Extravehicular Mobility Unit) suits will be worn by Artemis III crew members during NASA’s planned 2026 mission to the Moon. The suits have been made using long-lasting and high-performance materials that are designed to withstand the extreme conditions of space.

By joining this collaboration, Prada, known for its high fashion, is shifting into a highly symbolic arena of technological advancement. This will likely help position it at the forefront of sustainability and technology discussions – at least in the minds of consumers.

Prada itself has varying levels of compliance when it comes to meeting sustainability goals. The Standard Ethics Ratings has listed it as “sustainable”, while sustainability scoring site Good on You rated it as “not good enough” – citing a need for improved transparency and better hazardous chemical use.

Recently, the brand has been working on making recycled textiles such as nylon fabrics (nylon is a part of the brand DNA) from fishing nets and plastic bottles. It also launched a high-fashion jewellery line made of recycled gold.

Prada’s partnership with Axiom signifies a milestone in fashion’s ability to impact on high-tech industries. Beyond boosting Prada’s image, such innovations can also lead to more sustainable fashions.

For instance, advanced materials created for spacesuits could eventually be adapted into everyday heat-resistant clothing. This will become increasingly important in the context of climate change, especially in regions already struggling with drought and heatwaves. The IPCC warns that if global temperatures rise by 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, twice as many mega-cities are likely to become heat-stressed.

New innovations are trying to help consumers stay cool despite rising temperatures. Nike’s Aerogami is a performance apparel technology that supposedly increases breathability. Researchers from MIT have also designed garment vents that open and close when they sense sweat to create airflow.

Similarly, researchers from Zhengzhou University and the University of South Australia have created a fabric that reflects sunlight and releases heat to help reduce body temperatures. These kinds of cooling textiles (which could also be used in architecture) could help reduce the need for air conditioning.

One future challenge lies in driving demand for these innovations by making them seem fashionable and “cool”. Collaborations like the one between Prada and Axiom are helpful on this front. A space suit – an item typically seen as a functional, long-lasting piece of engineering – becomes something more with Prada’s name on it.

The collaboration also points to a broader potential for brands to use large attention-grabbing projects to convey their sustainability credentials. In this way they can combine spectacle with sustainability. The key will be in making sure one doesn’t come at the expense of the other.

![]()

Alyssa Choat does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.